The Story of Conn in the world of Phoenix

Understand the request-response lifecycle of a single Phoenix page request.

About a decade ago, when I was doing Drupal consulting, one of my interest was to study the full http request-response cycle of Drupal. Later on, I tried to do a same study for a Rails app. Both of these were incomplete due to the complex nature of the frameworks and of course limited by my knowledge of those frameworks at the point. However, though incomplete, whatever I learned in understanding the request-response life cycle in those frameworks proved very useful for me to understand the framework better and to make best use of it.

Since Elixir and Phoenix are valuing explicitness in code, I thought it would be a comparatively easier task to learn Phoenix request-response cycle. Last week, I sat down to study it with great success (albeit with a little struggle in understanding metaprogramming code in the framework) and in this post I am going to walk through the lessons learned. The entire study can be summarized as a quest to answer the following three broad questions:

- Getting In - When I hit an URL in my browser, which code in my phoenix_app gets executed first, and how does it get triggered?

- Processing - What is the journey of my request data in phoenix_app?

- Getting Out - Which code returns the response?

What are you going to learn?

Before I jump in, here is what I am going to tell in practical terms:

Let’s create a new phoenix app:

1

2

3

4

5

6

❯ mix phoenix.new my_phoenix_app

[....]

❯ cd my_phoenix_app

❯ mix phoenix.server

Now open up http://localhost:4000/, and you will be greeted with a welcome message.

Now the reminder of this post is about what happened from the moment you started your request http://localhost:4000/ to the moment you saw the welcome message on the screen.

Who is it for?

This post dives deep into the terminologies used in Elixir and Phoenix. If you are completely new to Elixir or Phoenix, you might have difficulty following the post. I expect the reader to be someone who has already used Phoenix at least to tinker with, if not used in production.

The Goal

This post is structured as a story telling. If you played with Phoenix for a bit, you might have seen this conn required in almost all places of your application code. It’s conn in the routes, controllers, views, plugs and @conn in templates. Have you wondered why is this conn all over? Where does it come from? What does it mean? You are not alone.

The conn that I explained above is the protagonist of our story, a mysterious guy who comes into life when you make a request to a phoenix app and dies when the response is sent out. My intention is to enable you to read this post as a story, though it has references to huge code blocks.

This post is going to be long but I promise to make your understanding of internal working on Phoenix better by the end of this post (unless you are José Valim or Chris McCord or Bruce Tate or any one in the core team). With that knowledge, I hope you will truly appreciate how Phoenix works and be a better Phoenix developer.

Character Introduction

This story is about Conn, the guy who carries the whole request-response in Phoenix. But like any story, there are many other complex characters and settings that needs to be understood before we full understand who the protagonist is. Let me introduce you to the story setting, and the characters in this story that you will encounter.

Story Setting

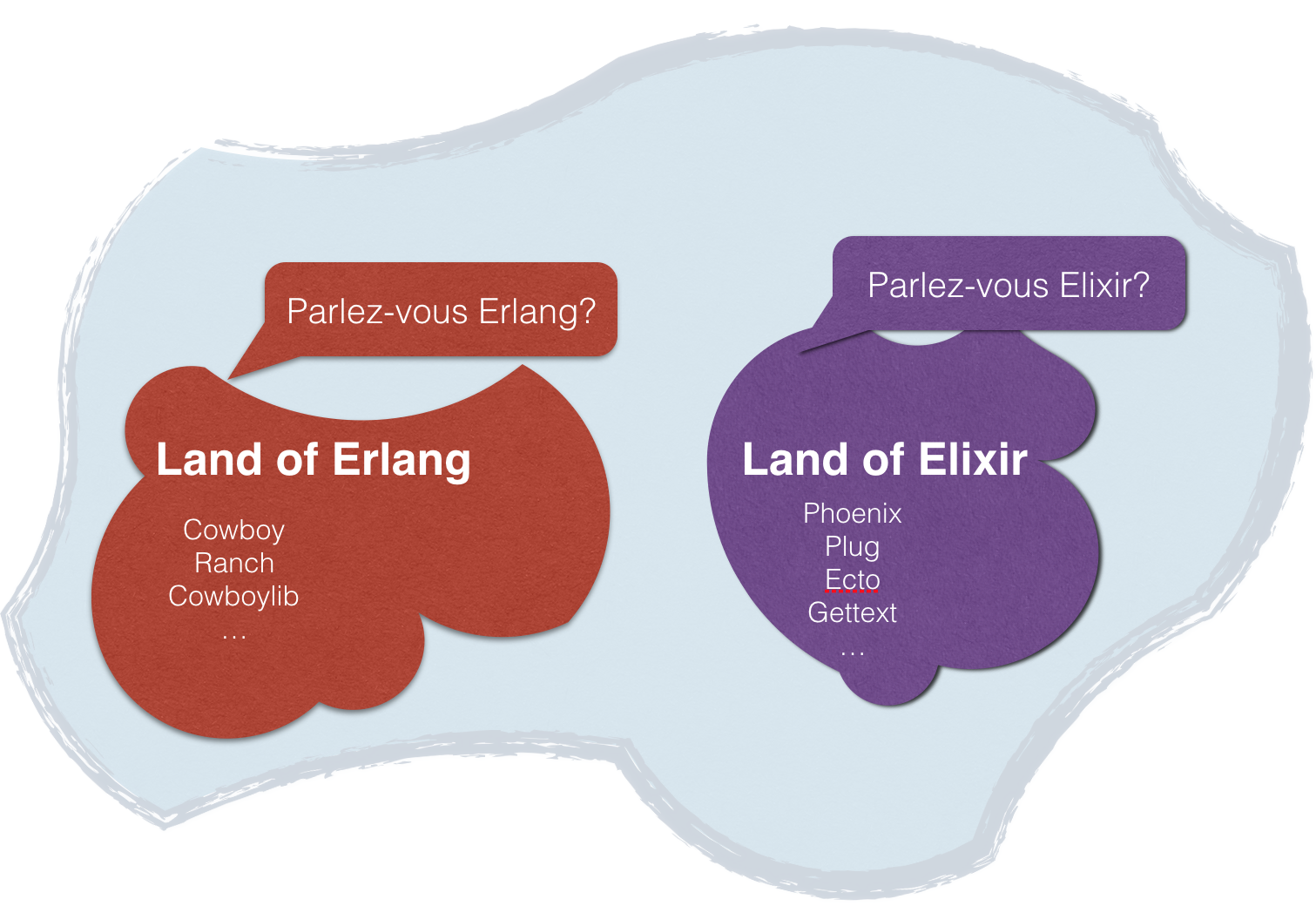

This story happens in the world of Phoenix which comprises of two lands:

The land of Erlang - dominated by cryptic yogis with lots of magical powers (called BEAM) who speak the language Erlang which takes years of penance to master.

The land of Elixir - dominated by evolutionary new age yogis who speak the more easily understandable language Elixir but connecting to the same magical power BEAM.

Characters

-

Cowboy - is an erlang web server comparable to nginx or apache but with a difference.

-

Ranch - is a dependency of Cowboy and is used for creating a connection pool. If you don’t understand what a connection pool is, don’t worry about it. Just understand that Cowboy needs it. You can still get along with the story without understanding ranch.

-

Plug - is an Elixir library that helps to easily interact with cowboy without having you speak the erlang language.

- Various Plugs

- MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint - The Gatekeeper of your application. Only Conn can come in or go out.

- MyPhoenixApp.Router -

- MyPhoenixApp.Controller

- MyPhoenixApp.View

- Conn - The guy who comes into life in your application with a request at the Endpoint and goes around your application for a shopping and leaves the Endpoint after shopping.

Cowboy

Of all the characters listed above, cowboy deserves an additional introduction. Cowboy plays in the same field as Nginx or Apache. While Nginx or Apache web server map a file on the disk to every HTTP request and execute the file, cowboy maps every HTTP request to an erlang module.

For e.g.., Nginx uses root_path and apache uses DocumentRoot to map the file on disk that can respond to the HTTP request.

1

2

3

4

5

6

# A simple nginx configuration

server {

listen 80;

root /var/www/example.com/public_html;

server_name example.com;

}

1

2

3

4

5

# A simple apache configuration

<VirtualHost *:80>

DocumentRoot "/var/www/example.com/public_html"

ServerName example.com

</VirtualHost>

Cowboy works differently in the sense, it has no idea of the files on disk. What it cares about is mapping an HTTP request to an erlang module. In the configuration below, it maps every request to MyApp.Cowboy.Handler module.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

dispatch_config = :cowboy_router.compile([

{ :_,

[

{:_, MyApp.Cowboy.Handler, []},

]}

])

{ :ok, _ } = :cowboy.start_http(:http,

100,

[{:port, 8080}],

[{ :env, [{:dispatch, dispatch_config}]}]

)

Take home point is that cowboy needs a module specified as the handler for all request. It’s this property of cowboy that the Plug library exploits for good and enables Phoenix to process requests as it works now.

Genesis - Let there be Phoenix

Now that we have covered most of the basics, we just need to know how to start an Elixir OTP app.

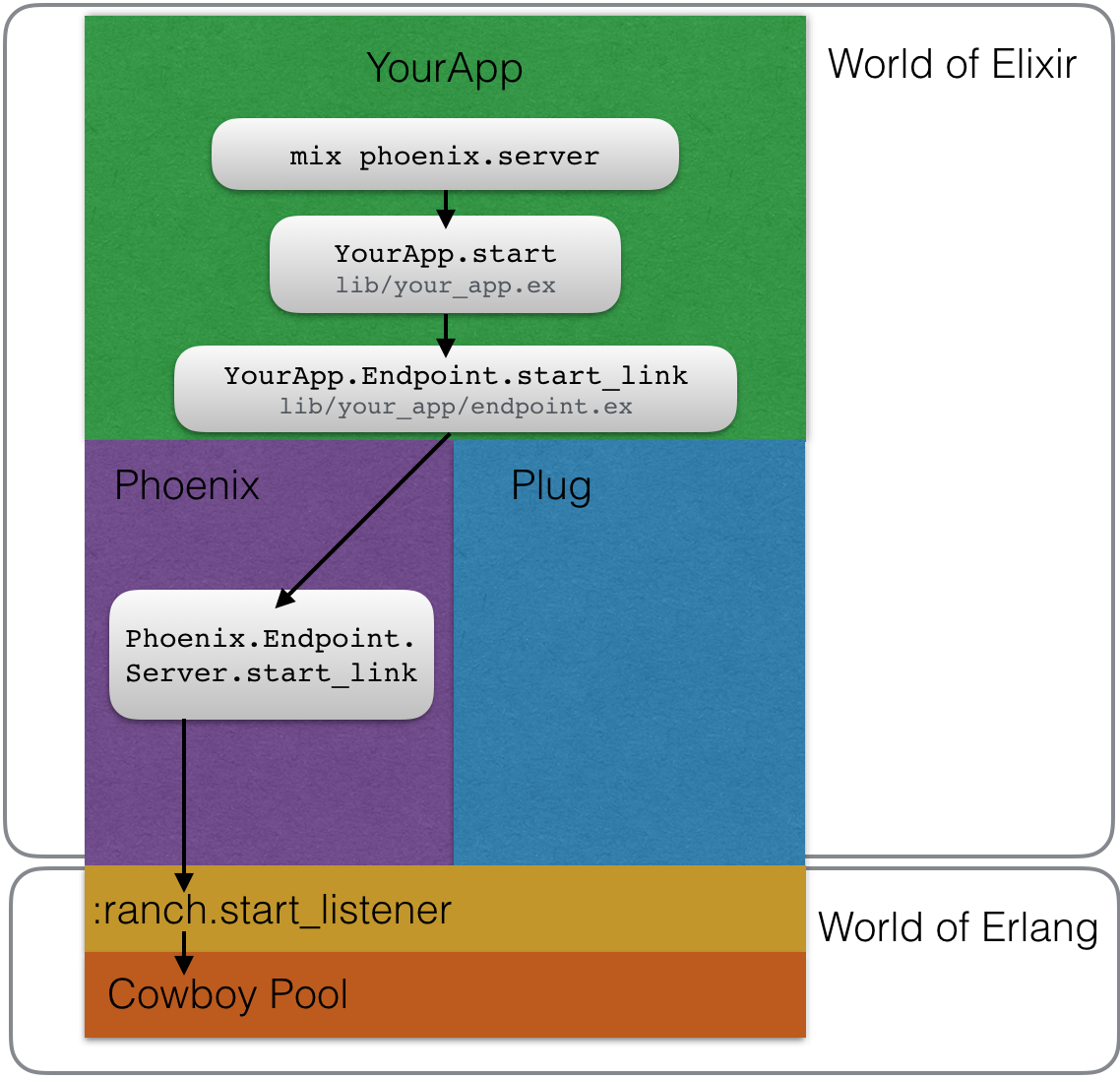

When you give the command

mix phoenix.new my_phoenix_app

what you are doing is creating an Elixir OTP app. Your phoenix project is just another Elixir OTP app and there by follows the same rules that apply to any OTP app. Explaining what is OTP is yet another story on its own, so if you don’t know what OTP is already, it’s sufficient to know it’s one of the common type of Elixir projects.

When you give the command

mix phoenix.server

what you are actually doing is playing God, blowing down life-giving breath. You just have created a world of Phoenix that is ready to accept any request and give out response. Let’s see how this world starts its life.

Remember, your phoenix project is an Elixir OTP app. So it works exactly like any other OTP app as described below.

Inside your mix.exs file of your phoenix app, there is function called application

1

2

3

4

5

6

# in mix.exs

def application do

[mod: {MyPhoenixApp, []},

applications: [:phoenix, :phoenix_pubsub, ...]]

end

This function returns a keyword list with keys :mod and :applications

When you run mix phoenix.server, Elixir starts all the applications listed in the :applications in the order mentioned and then starts the current phoenix project. When we say starting an application, what is actually being done is a call to a function named start in the module given in :mod.

So in our phoenix project, our mix.exs file mentions the module name MyPhoenixApp which is generated automatically when we created our phoenix project. This module defines the required function start. So when we run either iex -S mix or mix phoenix.server this start function gets invoked.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# in lib/my_phoenix_app.ex

def start(_type, _args) do

import Supervisor.Spec

children = [

supervisor(MyPhoenixApp.Repo, []),

supervisor(MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint, []),

]

opts = [strategy: :one_for_one, name: MyPhoenixApp.Supervisor]

Supervisor.start_link(children, opts)

end

This function creates a supervisor process which monitors two child supervisor processes for Repo and Endpoint. A supervisor process doesn’t do any actual work, rather, it only check if the child processes are working or dead. Since our start function started two child processes, both of which are supervisors, it also means that these child supervisors have one or more workers or supervisors.

Since our quest is to learn about Conn, we don’t need to look further into Repo supervisor. It’s a supervisor to manage database connections.

Let’s dive into Endpoint supervisor. MyPhoenixApp Endpoint is defined as a module at lib/my_phoenix_app/endpoint.ex and it contains code as below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

defmodule MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint do

use Phoenix.Endpoint, otp_app: :my_phoenix_app

...

plug Plug.RequestId

plug Plug.Logger

...

plug MyPhoenixApp.Router

end

MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint is a child supervisor of your MyPhoenixApp supervisor, however you don’t see the required start_link function in Endpoint. How does it work then? Here comes the meta programming magic. The line use Phoenix.Endpoint, otp_app: :my_phoenix_app is a magic spell that does a lot of things in your Endpoint, and one of them is to define a start_link function dynamically with all the worker details your Endpoint needs to monitor.

One of the automatically defined workers for your phoenix app is an embedded ranch supervisor. This supervisor starts Cowboy process listening at port 4000 on localhost and is configured to pass all request to Plug.CowboyHandler.

At this point you brought the world of Phoenix into life, waiting to receive request at port 4000.

What is not captured in the above diagram is that Cowboy gets Plug.Adapters.Cowboy.Handler as the module that handles all request and also gets your phoenix application endpoint module as an argument. So effectively we have wired your phoenix app and cowboy through Plug.Adapters.Cowboy.Handler.

The Story of Conn

conn that you see in your phoenix app router, controller, views, and templates is infact a struct defined in Plug.Conn module. It has several keys to store exhaustive information about both request and response. Unlike other frameworks where there are separate objects to store request and response, Phoenix uses %Plug.Conn{} struct to store both request and response information.

Birth of Conn

When you make a request to http://localhost:4000 in your browser, the sequence of action goes as below:

Plug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handlerget called with the request information.- From the request information, the Handler creates the below struct filling in all request information. This is the birth of

connstruct.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

%Plug.Conn{

adapter: {Plug.Adapters.Cowboy.Conn, req},

host: host,

method: meth,

owner: self(),

path_info: split_path(path),

peer: peer,

port: port,

remote_ip: remote_ip,

query_string: qs,

req_headers: hdrs,

request_path: path,

scheme: scheme(transport)

}

Life of Conn in the Endpoint

Plug.Adapters.Cowboy.Handlerthen invokesMyPhoenixApp.Endpoint.callpassing in the newly createdconnstruct.- This module

MyPhoenixApp.Endpointgot passed as argument when we initially started our Phoenix server usingmix phoenix.server. -

Recall the

MyPhoenixApp.Endpointcode as shown at the beginning of this post. It contained severalplug THISlines:plug Plug.Static

plug Phoenix.LiveReloader

plug Phoenix.CodeReloader

plug Plug.RequestId

plug Plug.Logger

plug Plug.Parsers

plug Plug.MethodOverride

plug Plug.Head

plug Plug.Session

plug MyPhoenixApp.Router - Also the first line in our Endpoint

use Phoenix.Endpoint, otp_app: :learnphoenixdefines a function calledcallin our module. This enables thePlug.Adapters.Cowboy.Handlerin the previous steps to invoke ourEndpoint.call. - Due to how

Plugis designed, ourconnstruct now passes through each of the plug functions in the order they are defined. Each plug in the chain makes modification to theconnstruct if needed and passes on the modified struct to the next plug in the chain. - Notice that there is a plug

MyPhoenixApp.Routerat the end of this chain. There theconnstruct takes a new turn in its life. - All through the life at Endpoint,

connstruct was modified with priliminary information about the struct. Now when it entersMyPhoenixApp.Router, it will start doing the actual work of getting the requested data.

Life of Conn in Router

Let’s look at our MyPhoenixApp.Router

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_flash

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

scope "/", Learnphoenix do

pipe_through :browser

get "/", PageController, :index

end

- When

connis passed on to Router, the router has two main function to do.- First find the matching route based on the request path present in

connand store that function inconnstruct. This action is called matching. - The next one is to dispatch the matching function. But before it calls the stored function, it executes all the stored pipelines for the given scope. For the path “/”, the pipeline is

:browser, so the router first passes on the conn to all the plugs inside:browserand then the resultingconnis then passed on to the stored dispatch function inconn. The stored dispatch function for/in the above router is

- First find the matching route based on the request path present in

1

2

3

4

5

fn conn ->

plug = MyPhoenixApp.PageController

opts = plug.init(:index)

plug.call(conn, opts)

end)

Life of Conn in PageController

- If you look at the last function call, router is actually calling

MyPhoenixApp.PageController.init. However, we don’t have this function defined. Again, this function is automatically defined by meta programming in all Controllers that have this lineuse MyPhoenixApp, :controllerat the top. - The auto defined

callfunction’s responsibility is to check if there are any other plugs defined in the controller level and if yes call them in sequence passing in theconnstruct and at the end call the controller action:indexwhich got passed asopts. - Inside a controller action, there is a call to

render conn, "index.html". Since no view name is mentioned in this call, view name is automatically derived from the controller name which in this case isPageView. - We haven’t defined any functions in

PageViewmodule. However, due to metaprogramming magic, all files that are present inweb/templates/pageare converted as functions insidePageView. So our template atweb/templates/page/index.html.eexgot converted into a function insidePageViewas

1

2

3

def render("index.html", assigns) do

# contents of index.html as string which gets pared with EEX engine with the variables assigned in `assigns`

end

Final rituals for our Conn

Function call in the view layer is the last one in our long list of invoked functions from Plug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handler. However, where does the function return this value? To answer that we need to look at how the Plug architecture works. Our first plug call started at Plug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handler as explained in the “Birth of Conn” section above which called Endpoint.call. This call happened from the function that cowboy server triggered when the request originated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

# A simplified version of Plug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handler

def cowboy_server_handler(req, args) do

conn = create_conn(req) # create a new conn struct from the request information from cowboy.

endpoint = args[:endpoint] # endpoint is actually MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint

conn = endpoint.call(conn) # invoke the call function in MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint.

send_data(conn) # this sends the data back to cowboy in the format that cowboy understands.

end

Our Endpoint plug functions so far looked like a sequential call. However, they are not sequential, rather nested. The actual nested function call of our Endpoint plug is as below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

case(Plug.Static.call(conn, {[], {:my_phoenix_app, "priv/static"}, false, false, "public, max-age=31536000", "public", ["css", "fonts", "images", "js", "favicon.ico", "robots.txt"], [], %{}})) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Phoenix.LiveReloader.call(conn, [])) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Phoenix.CodeReloader.call(conn, reloader: &Phoenix.CodeReloader.reload!/1)) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Plug.RequestId.call(conn, "x-request-id")) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Plug.Logger.call(conn, :info)) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Plug.Parsers.call(conn, length: 8000000, parsers: [Plug.Parsers.URLENCODED, Plug.Parsers.MULTIPART, Plug.Parsers.JSON], pass: ["*/*"], json_decoder: Poison)) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Plug.MethodOverride.call(conn, [])) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Plug.Head.call(conn, [])) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(Plug.Session.call(conn, %{cookie_opts: [], key: "_my_phoenix_app_key", store: Plug.Session.COOKIE, store_config: %{encryption_salt: nil, key_opts: [iterations: 1000, length: 32, digest: :sha256, cache: Plug.Keys], log: :debug, serializer: :external_term_format, signing_salt: "79la9kyY"}})) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(MyPhoenixAPp.Router.call(conn, [])) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

conn

_ ->

raise("expected MyPhoenixAPp.Router.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.Session.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.Head.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.MethodOverride.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.Parsers.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.Logger.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.RequestId.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Phoenix.CodeReloader.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Phoenix.LiveReloader.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

_ ->

raise("expected Plug.Static.call/2 to return a Plug.Conn, all plugs must receive a connection (conn) and return a connection")

end

If you are brave enough, you can venture into traversing the above code. It’s actually not so hard as it looks. A simplified version is below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

case(Plug.Static.call(conn, args)) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

case(MyPhoenixApp.Router.call(conn, [])) do

%Plug.Conn{halted: true} = conn ->

nil

conn

%Plug.Conn{} = conn ->

conn

_ ->

raise("error")

end

end

_ ->

raise("error")

end

This is basically saying, if the static plug sets the conn’s :halted key to true value, then don’t do anything. If not, call the next plug function with the new conn.

Due to this nested structure, whichever is the last plug function invoked, the value is returned back to Plug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handler which triggered this nested call. Now the conn struct contains both the request and response information having passed through all layers of your phoenix app, it’s now ready to respond to cowboy request. Plug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handler invokes :cowboy_req.reply/4 with http_status, headers, body, request pulled from the conn struct and that marks the end of our conn struct.

Revisting our questions

-

Getting In - When I hit an URL in my browser, which code in my phoenix_app gets executed first, and how does it get triggered?

The answer is

MyPhoenixApp.Endpoint.call. This call was made fromPlug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handlermodule which interfaces with the underlying Cowboy server. -

Processing - What is the journey of my request data in phoenix_app? Request data got wrapped in

connstruct inside and got passed on toEndpoint.call. From there the journey ofconnstarts, passing through all the plugs defined in Endpoint, then to Router, Controller, View. -

Getting Out - Which code returns the response? The processed

connwas received back atPlug.Adapter.Cowboy.Handlerwhich then sends the response to Cowboy server by triggering:cowboy_req.reply/4

Revisiting our goal

The goal of this post is to

- better understand the internal working of Phoenix

- be a better Phoenix developer

I hope that in this post I have explained what the Phoenix core team members frequently say “it’s plug all the way down” in Phoenix. From the initial call to Endpoint.call it was all calls to plug functions. This I hope helped you to understand the internal working on Phoenix. And as a side effect, I also believe that it will help you to make better decisions on what is possible with Phoenix request cycle and how to intercept the request-response cycle with your own plugs.

I hope that I have contributed towards this goal in this post. If you find any mistake in the post or any section not clear enough, feel free to comment below and I shall try my best to answer every question posted.